DOG BLOG

Musings

Sighthound Necessities

The Importance of Free Exercise for Large Sighthounds

Sighthounds love to gallop, to chase and stretch out. They experience unmistakable, sheer glee as they are bending, folding and leaping. You can see it in their expression. So, why is it that so many of these admirable Sighthounds are found living in unsuitable homes, having little or no fenced, secured acreage?

The Importance of Free Exercise for Large Sighthounds

Sighthounds love to gallop, to chase and stretch out. They experience unmistakable, sheer glee as they are bending, folding and leaping. You can see it in their expression. So, why is it that so many of these admirable Sighthounds are found living in unsuitable homes, having little or no fenced, secured acreage? As responsible fanciers and hobbyists, fulfilling their needs should be a primary concern when we place our hounds in their new, permanent homes. Our stewardship of these unique breeds obliges us to proceed with utmost care and concern while considering a new home.

I am not an elitist who snubs a potential puppy owner, turning up my nose at those whose accommodations are not ideal for our Sighthounds. On the contrary, I encourage them to contact me so that I may educate them about the exceptional needs and characteristics of our breeds. More importantly, though, I am aware that urban population growth has changed significantly over the past 60 years in our nation. We all live in an evolving landscape. "Metropolitan areas are now fueling virtually all of America's population growth," as reported in the Washington Post by Emily Badger. In an interesting article, unwittingly she corroborates what many conscientious breeders have realized, that ideal Sighthound companion homes are harder and harder to find. Small population centers with less than 50,000 people have had infinitesimal growth changes. Rural populations have dwindled. Today, one in three Americans lives within the metro areas of 10 cities — or just a few spots on the nation's map. The relevancy of the census data must not be under-appreciated, as this means that, slowly but surely, there are fewer opportunities for us to find homes for our galloping hounds.

The reality I face is that significantly more inquiries than in the past hail from people with no land. From the 36 puppy requests I have received in the past six months alone, 32 (90%) were from persons who did not have what I consider sufficient area to accommodate a Sighthound. Furthermore, this percentage includes some individuals who either currently have or previously owned a Sighthound — from another breeder — in their home.

I readily anticipate the question "How much land does she require?" Ideally, a home for a large breed Sighthound should have at least one acre of property secured with breed-appropriate fencing, but from my experience of three-plus decades in dogs, this often seems like an unrealistic requirement. A bare minimum of half an acre of open land, again properly fenced, not including the house, is my condition. I have received some requests from potential puppy buyers who own half an acre of land that included the home as well as an accessory building; one memorable inquiry offered half an acre of land that included the house, an in-ground swimming pool with a cabana and what appeared to be a Bocce ball court. All that was left was a postage-sized space for the hound to defecate in, without any area to run and play.

I politely refuse to place my large Sighthound puppies in these environments, notwithstanding the usual promises of the on-lead daily exercise that the hound would receive. You must be familiar with this type of dialog. A potential owner asserts that, although there is no acreage for free running, they regularly walk so-and-so many miles and they also live near a park where the hound can be off-lead. Almost all of us understand that Sighthounds are not candidates for off-lead running on public grounds. Simply, this is a hazardous situation due to their prey drive — a good subject for another article I plan on writing.

As for good intentions and best-laid plans, how many times has life thrown us curve balls? Life has a habit of bringing unexpected, unwanted changes or accidents. If a hound’s principal caregiver is injured or becomes ill, ultimately the hound is handicapped as well. The Sighthound will no longer have lengthy walking excursions to release energy and obtain needed exercise. Likewise, if an owner’s work responsibilities increase, this almost invariably impacts the time spent with the hound on a leash. Regrettably, because the properly fenced acreage was initially sacrificed, the hound does not have an area for self-exercise and running. So, ultimately, he suffers.

Self-exercise for a Sighthound is not only the freedom to stretch out his legs, to leap, twist and turn, all of which releases energy. It also is key to a Sighthound's development, both physical and mental. Strong, hard muscles are vital to proper maturation and longevity, as well as to protecting the body from unwarranted injuries. Secured exercise provides valuable mental stimulation: simply, it is good for a Sighthound's psyche or soul, mind, and spirit. His personality and character can develop to their full potential, which is especially crucial in the powerful, giant Sighthound breeds where it is especially important that they must be even-tempered and well adjusted.

Some may feel that placing companion-quality Sighthounds in a loving home where they receive individualized attention is far better than allowing these hounds to languish in a kennel environment. To a great extent, I agree, but the compromises that some breeders make are worrisome. The trade-offs are unfair and incompatible for galloping hunters bred for running, especially when we hear that Wolfhound puppies are placed in townhomes, not as temporary but as permanent quarters. Where is the line drawn for responsible breeders to reject a potential home?

Others may belittle this discussion by stating that one cannot keep every puppy, and who am I to decide what is enough space for a Sighthound to live on comfortably? Some may claim that leashed exercise is sufficient for our hounds and that many of the hounds exercised only on leash are in better physical condition than a hound with acreage. Now and again, this statement could prove true. Having been a longtime Wolfhound fancier, I know from first-hand experience that, on occasion, some Wolfhounds will not use the available space for running but just sit at the gate. Despite having one hundred fenced acres, there they were, lying on the opposite side of the fence gate waiting for me. On the other hand, Sighthounds living on considerably less acreage may happily explore and bound about their areas.

Today's average homeowner does not have acres of property, in fact, much, much less. For those fortunate to have some but still acceptable amount of property, it can be transformed to accommodate a galloping hound, as long as the homeowner is willing to do so. Indeed, the initial fencing investment is costly, but our sighthound breeds can be expensive. Expenses are a certainty all prospective puppy owners must be prepared for, though, in the end; these hounds are well worth the investment.

Returning to the subject of alternative leashed exercise, I frequently pose this logical question. Which athlete would have the better overall cardiovascular condition? A person who runs or walks daily? Granted, walking is far superior to no workout and also offers benefits. I always recommend puppy owners frequently walk with and socialize their hounds, regardless if they have one or ten acres of fenced land. However, what about the muscle-toning obtained while the Sighthound enjoys fenced but free exercise that is not achieved by just leash-walking? While placing a Sighthound, maybe future fitness is not a priority for some breeders, despite the health benefits. If care, love, and clean accommodations are all that a breeder requires from their puppy owners, they are, in my opinion, doing a disservice to our Sighthounds.

If we cannot respect these breed's noble heritage, why then do we bother having them? There is a myriad of other Group breeds who require only small areas and some exercise who are entirely satisfied residing on the couch. In fact, AKC generates several suggested dog breed lists that correspond to homeowners lifestyles. You can see the links to these from my website page, Irish Wolfhound Breed Character. Several times in these past years, after I called attention to inadequate property conditions and discussed such concerns with a few rational, prospective owners who had fallen in love with the Irish Wolfhound breed, they did, in fact, resist the urge of instant gratification. These people understood my objections; they respected my advice and my decision, recognizing that it would be simply unfair for them to have a giant, galloping hound. As a long-standing breed custodian, a rational resignation like this is one of the best things that I could wish for my wonderful sighthound breed, the Irish Wolfhound.

Ballyhara Candid photos from recent Potomac Specialty Show

Here are a few candid photos of my Irish Wolfhounds from a recent specialty show.

Re-posting my blog post "Happy Holidays & Westminster Musings"

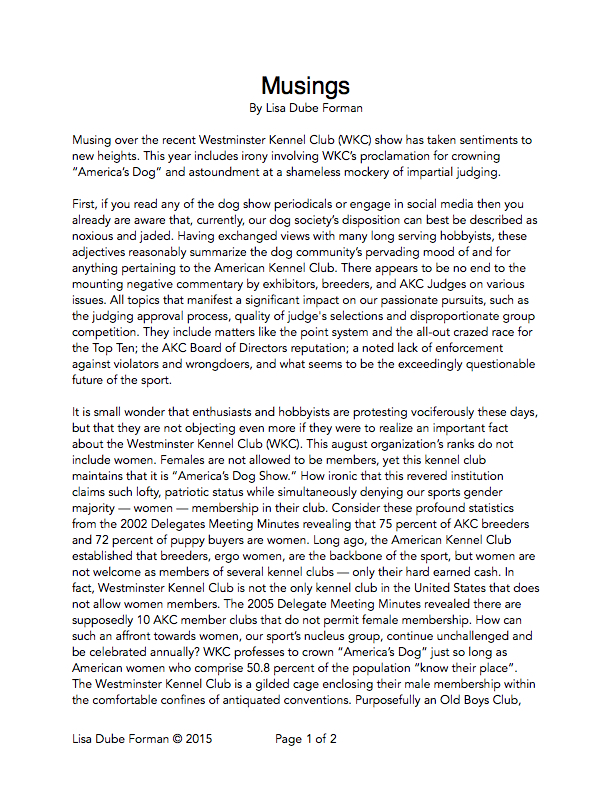

For me, it is disappointing that another year has rolled past without what I feel are necessary changes to the membership roles of the Westminster Kennel Club.

If you are unaware, this venerable club is Men Only -- NO WOMEN ALLOWED AS MEMBERS.

As I was performing chores this morning my thoughts turned to the upcoming Westminster Kennel Club dog show on February 15-16, 2016. For me, it is disappointing that another year has rolled past without what I feel are necessary changes to the membership roles of the Westminster Kennel Club. If you are unaware, this venerable club is Men Only -- NO WOMEN ALLOWED AS MEMBERS. Yes, you read that correctly. This dog club is not the only holdover in the United States, but certainly is one of the most prestigious. Here is an excerpt from my article I penned in March 2015, titled "Musings".

This august organization’s ranks do not include women. Females are not allowed to be members, yet this kennel club maintains that it is “America’s Dog Show.” How ironic that this revered institution claims such lofty, patriotic status while simultaneously denying our sports gender majority — women — membership in their club. Consider these profound statistics from the 2002 Delegates Meeting Minutes revealing that 75 percent of AKC breeders and 72 percent of puppy buyers are women. Long ago, the American Kennel Club established that breeders, ergo women, are the backbone of the sport, but women are not welcome as members of several kennel clubs — only their hard earned cash...

That the majority of AKC dog show participants are of the female gender and are, still, taking a backseat role in the governance of this sport in the year 2016 should be alarming. That in the year of 2016, while humanity is pursuing deep space exploration and a colonization of Mars in the advent of a successful, historic landing of reusable rockets back on Earth, the Westminster Kennel Club still clings to its antediluvian traditions of banning women from membership.

How can such an affront towards women, our sport’s nucleus group, continue unchallenged and be celebrated annually? WKC professes to crown “America’s Dog” just so long as women who comprise 50.8 percent of the American population “know their place”. The Westminster Kennel Club is a gilded cage enclosing their male membership within the comfortable confines of antiquated conventions. Purposefully an Old Boys Club, they celebrate and preserve their gender bias practices. Insofar as women, well, women are only necessary and welcome when the club needs exhibitor participation.

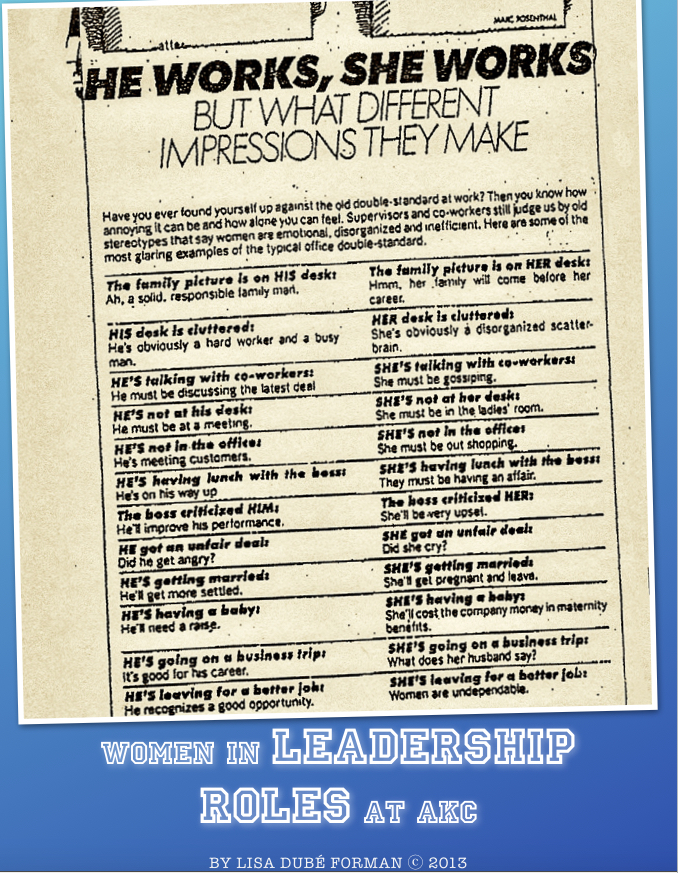

While we celebrate the holidays and give thanks for all that we have in our lives -- ponder on this contradiction and dismissal of women's equality and our rights. Consider that if women took a stand against such blatant gender discrimination, we can make an enormous difference. We did so with the women's suffrage movement resulting in the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution ratification in 1920 guaranteeing all American women the right to vote. In the sport of purebred dogs, it is unjust that women have been continuously denied administerial duties of the American Kennel Club Board of Directors. An excerpt from my investigative article "Women in Leadership Roles at the AKC" follows:

Let us consider first the little known historic, consequential and stunning fact that AKC did not admit women to serve in the Delegate body until the 1970s. On March 12, 1974, a motion to allow women to serve as delegates was seconded and carried by a vote of 180 to 7.

Furthermore, that the administrative part of the AKC has just one female President over its entire lifespan since its formation in 1884, and to date, there has never been a female Chairwoman of the Board of Directors is simply a travesty of equality.

Before I sign off from this post, I also would like to remind people of what had transpired during the 2015 WKC dog show. Another excerpt from my "Musings" article.

Yet, unfairness or bias was not limited to the organization’s constituency roll. A particular incident took place during breed judging that reinforces the dog show community’s prevailing, cynical state of mind. No wonder fanciers are disgusted, throwing their hands up in exasperation. Actions that did not merely give an impression of but created a dense cloud of impropriety.

The ethical transgression transpired when a Judge presided over a Best of Breed assignment which included a dog this judge very recently used at stud. The litter sired by this entry reportedly was whelped already. Destroying any sense of impartiality, the judge proceeded to award this stud dog Best of Breed over the competition and also awarded Select Dog to yet another dog they previously used at stud as well! The basis of sportsmanlike competition is to adjudicate with neutrality, imputing ethics, honesty, and common sense. Instead, this incident exposes a lack of common decency and an illiteracy for the Rules, Policies and Guidelines for dog show judges.

This is an unambiguous example of Conflict of Interest. AKC dog show judges are responsible for situations such as this that require the judge to excuse an exhibitor for causes even known only to them and they were obligated to recognize that a conflict of interest existed. As for the exhibitor(s) who intentionally exhibited their stud dog under this particular judge? The responsibility for entering dogs that are ineligible or create a conflict of interest lies with the exhibitors, so says the AKC Rules & Policies Handbook for Conformation Judges. In fact, the Handbook states that awards won may be canceled, and exhibitors with repeat violations may receive reprimands or fines. Further exacerbating the situation, this competition was video streamed live throughout the world! A great many breed fanciers watched in disgust as the judging unraveled. It most likely has not nor perhaps ever will dawn on the judge that they would have gained a great deal of respect, if, in fact, they had exercised their right and performed their duty by excusing the violating exhibitors from the show ring. However, it is too late as now their repute is justifiably and seriously challenged.

As for the other exhibitor(s) competing in the show ring, in my opinion, they should have filed a complaint without delay with the AKC Executive Field Representative who was visibly in attendance. Until our sport participants slip their binds of submissiveness and possess the courage of one's convictions, violator's such as these described will continue to bully, unhindered. Here are links to both of my articles discussed above.

Posterior Judgement

Fanciers and Judges make a great to-do over the dog’s hindquarters but can they really recognize a sound, strong pelvic girdle and pelvic limb construction? Although breed blueprints revolve around specialization demanding differing angles to include descriptive terms, such as sweep of stifle or great length from hip to hock, unimpaired hindquarters construction is the same, no matter the breed. First,...

Fanciers and Judges make a great to-do over the dog’s hindquarters but can they recognize a sound, strong pelvic girdle, and pelvic limb construction? Although breed blueprints revolve around specialization demanding differing angles to include descriptive terms, such as sweep of stifle or great length from hip to hock, unimpaired hindquarters construction is the same, no matter the breed.

First, we start with the basic technicalities to differentiate the thoracic from the pelvic limbs. The pelvic limbs are fused and joined to the vertebral column, whereas the thoracic limbs are connected by muscle and ligaments, that is to say not bone to bone. The pelvic limbs are heavily muscled, longer and more angular than the thoracic limbs as they are responsible for propulsion. Pelvic limb movements surge or throw body weight forward, and the thoracic limbs catch and support this weight no matter what the stride and gait. Please note that stride and gait are not the same but more on this in another essay. One more fundamental is that the arrangement of the pelvis girdle and rump muscles enables the simultaneous extension of the hip, stifle, and hock. I will delve into regional musculature in another series.

Moving on, the strength of the pelvic girdle and limbs, length, and angularity of its bones and quality of muscling, in almost all cases, ultimately determines successful running speed. Because the dog species are carnivores, Mother Nature constructed him for running. Unmistakably, humans have intervened in evolution creating significant variations in the species and their functions. Some breeds have substantially limited running abilities, i.e., today’s Bulldog, Pekingese. Despite this, even the Bulldog’s hind end should be strong and muscular.

Many fanciers have taken a great liberty, far too much, redesigning the hindlimbs. Frequently we see improperly angled croups, plus over and under angulated hindquarters. Evaluating ‘hindquarter angulation’ involves two methods, yet often fanciers confuse the two or sometimes do not consider the other. The first is determining the angle of the pelvis from the horizontal called the pelvic slope. To determine pelvic slope we estimate a straight line from the forward part or crest of the ilium, to and through the ischial tuberosity. This line intersects with the horizon, therefore, creating a determinable angle. The most significant point is that this slope of the pelvic girdle can directly affect the progression and ability of the hindquarters forward-drive and thrust, otherwise known as propulsion. A steeply angled pelvis usually will restrict back reach locomotion.

The second process of determining hindquarter angulation is estimating the stifle joint angle. This angle is created and defined by two lines of intersection. One line is running centerline through the femur that is articulating from the hip bone to the stifle (knee joint), and the other line runs centerline through the tibia bone which articulates with and is connected to both the stifle and the tarsal joint (hock). Notably, the tibia is one of the major weight-bearing bones in the hindquarters. This method is standard in ascertaining symmetry between the forequarter and hindquarter angulation establishing if a dog is balanced.

The average, desirable stifle joint angulation for functioning dogs is 90-110 degrees. Simplifying the term ‘overangulated’ is when the angles of the femur and or the tibia themselves are set too sloping. An angle created by the femur through the axis of the tibia that is narrow, or more closed, is less than 90 degrees and is over angulated. In contrast, open angles might be more than 110 degrees where such a straightened femur and tibia do not generate rear power and drive. Invariably, in numerous breeds we see an unequal length of bones in the hindlimbs where the tibia bone is both too long and steeply sloped. This faulty engineering and redesign draws out the distal (lower) tibia, tarsal joint and rear feet, placing them dramatically behind the ‘seat bones,’ thus, greatly weakening the rear assembly’s capacity, thrust, and strength.

I repeatedly emphasize that the angle of the pelvis is very influential. Since the pelvic angle affects the width of the stifle and first thigh, a faulty slope limits the area for muscle attachment, and the dog has narrow thigh muscles. This is because many important muscles and tendons originate, are housed and attached on the femur, one of the strongest and longest bones in the rear. Also, consider the width of the second thigh and the lack of resulting in the phrase, weak second thighs. Second thighs are located below the knee joint and should be broad on almost all dogs. Weak and narrow thigh muscles do not show promise of speed or power.

If the dog has a weak or poorly constructed posterior, the dog is handicapped. Many breeders are careless, often planning matings based on conformation show wins without much thought to the pesky details of anatomy. Some casually believe that trends, such as over angulated hindquarters, results in accumulating more ‘wins’ then so be it, if that is what they have to do to win. In these cases, I reasonably question their posterior judgment.

Here, I have included photos depicting ideal canine hindquarters for an Irish Wolfhound. This bitch's hindquarters exemplifies strength, power, all in moderation at different ages. Neither over or under angulated, her pelvic angle along with her 30-degree croup angle regulating her tail set, are all ideal. For larger images, please click on the photo to enlarge in a lightbox. I included the 'going-away' photo illustrating exemplary rear hindquarter construction with sound, strong hocks. In this photo, the student or fancier can draw an imaginary line beginning at the center of the communal pads of the feet, up through the metatarsus and its hock joint, towards the hip socket and further, up through the crest of the ilium or hip bone. Another is of Jane's perfect, yes perfect, side gait. Rarely seen in Irish Wolfhounds, Jane's side gait was flawless, notice her rear feet comportment drive as she glides effortlessly.

Rosslare's Jane of Ballyhara 6 months of age

Rosslare's Jane of Ballyhara going away

Rosslare's Jane of Ballyhara gaiting 12 months. Credit Steve Surfman

Rosslare's Jane of Ballyhara 3 years

This article in a previous version first appeared on the Canine Chronicle website.

Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=38978

Fill & Station

Yes, pun intended, I mean filling station. My play on words is tailor-made for this discussion about dogs, particularly on their fill and station. Many hobbyists who are unfamiliar with the phrase ‘station’ are shaking their heads but then so is the notion about filling this station — filling what with what?

Yes, pun intended, I mean filling station. My play on words is tailor-made for this discussion about dogs, particularly on their fill and station. Many hobbyists who are unfamiliar with the phrase ‘station’ are shaking their heads but then so is the notion of filling this station — filling what with what?

In ‘dog speak’ it may help to know the origination of many expressions and anatomy parts we use in describing dogs was appropriated from horsemen. The native language such as station, withers, forehand, fetlocks, pole, ‘standing over a lot of ground’ are just a common few. Suffice to know that we just did not make this stuff up but the terminology has been in use for centuries.

Let us begin with the station a dog must have before we discuss fill. A station is a description we apply to a dog’s depth of chest or specifically, the measurement of the distance from the top of withers to the elbow as compared to the length of the dog’s leg. The distance determines if a dog is of a low or high station. Rather, if this distance largely eclipses the length of leg, we consider the dog ‘of low station.' A length of leg that is decidedly longer than the distance from withers to elbow is ‘of high station.' Ideal examples ‘of high station’ are sighthounds such as the Ibizan Hound and Saluki. Both have an appreciable length of leg with a shorter distance from their withers to the elbow. The Ibizan is both lithe and racy with deer-like elegance, and the Saluki brings down Gazelle, the fastest of the antelope family. In fact, the galloping sighthounds are to have extraordinarily, long legs and will have, for the most part, longer ratios of leg length as compared to their station. As a result, in general, they are appropriately of high station.

Low-station dogs such as the Basset, Dachshund and Dandie Dinmont — the latter being that he is uniquely low in the shoulder — are evident. However, one should also consider the Bull Terrier and the Pug as other fitting examples. Occasionally, a long-serving judge may comment that a dog has either excellent or poor station. To illustrate, if a judge faults a Rottweiler with a shelly appearance, then the judge has noted the dog is lacking the appropriate depth or also width of chest. The correct station for this working cart and drover breed should be 50 percent of the height of the dog. If the dog is too leggy or high in station, then he lacks the necessary chest depth and width measurements for the desired exercise and work tolerances.

One breed standard which refers to a decidedly filled chest or accentuated ‘spread’ is the Bulldog. Indeed, his spread is so valued and emphasized that when viewing the dog head-on, the rear legs are visible from the front. That is to say, if one were low enough to have an unobstructed view! At least, beginning in January 2014, the AKC announced that the Bulldog and Basset Hound judging will take place on the ramp in breed, group and best in show competitions so this may be of advantage to judges.

Function and performance demand quantity and quality fill in a dog’s station. Since fill is not just skeletal parts, particularly the prosternum and sternum (breastbone), but the muscling that protects the vital organs. The fill, more specifically the musculature collection which is both plentiful and very productive, surrounds the bow or keel. I speak of the serratus ventralis muscle, which is the sling and stabilizer of the thorax, the deltoids and brachial muscles, the descending and transverse pectorals, which advance the forelegs and draws the limbs in towards the axis or center line of the body, along with the deep pectoral muscle which stabilizes the forelegs. When a dog lacks the proper breed constitution, such as not being well-let-down in the chest — shallow — or he is narrow — lacking chest width and rib spring — the result is limited fill space. Often these faults also unmask concave or hollow chests, but all affect heart and lung capacity as well as gait. Pinched fronts are a definite fault as stated in the Giant or Miniature Schnauzer standards. As a result of this unique front, there is inadequate fill and a shallow brisket.

For the hunting breeds who dispatch game, poorly designed stations lacking fill put the hound at significant risk. Consider the Irish Wolfhound’s chest was also developed for impact and is part of the dog’s mass. It is another tool provided to injure the prey, but importantly, it is imperative to prevent injury to the wolfhound’s frontal portion of his skeletal structure. In this giant breed, a prominent but never excessive prosternum with a well-spread chest and quality fill operate as a shock absorber. All of this indubitably affects gait which is for another discussion on another day.

This bitch, for me, exemplifies Fill & Station. Even here as a yearling, she exudes being of 'high station.' She has quantity and quality fill in her station, but also her musculature collection is both plentiful and very productive surrounding her bow or keel. The lack of these essentials is, unfortunately, evident in many of today's Irish Wolfhound specimens. An important criterion that I seek out when judging is the fill between the breastbone. I know from first-hand experience that this is sadly lacking in too many Irish Wolfhounds. Disguised by combing hair forward, too many judges are deceived by ingenious grooming, and these judges do not see nor uncover concave or hollow chests with their examinations.

This article was first published on the Canine Chronicle website found at:

Short URL: https://caninechronicle.com/?p=40327

Feet Don't Fail Me Now!

Virtually all of the Dog Group breeds were propagated for and should be functional. Although today many argue that nearly every one of the breeds no longer fulfill their purpose, the truth is that for basic soundness of even our companions and family dogs, their feet factor into sustaining quality of life. Similar to a person whose feet have fallen arches, plantar fasciitis or muscle strains that cause constant discomfort and pain...

One cannot overstate the importance of the feet on our many breeds. I am discussing the shapes, phalanges, claws along with the digital and communal pads. A future essay will discuss the pasterns’ carpal and metacarpal bones.

Virtually all the Dog Group breeds were propagated for and should be functional. Although today many argue that nearly every one of the breeds no longer fulfill their purpose, the truth is that for basic soundness of even our companions and family dogs, the feet factor into sustaining their quality of life. Similar to a person whose feet have fallen arches, plantar fasciitis or muscle strains that cause constant discomfort and pain.

There are three standard shapes of canine feet. The round (cat-compact) foot has well-arched, tightly bunched or close-cupped toes with the center toes just marginally longer than the outside and inner toes. The oval (spoon-shaped) foot, is similar to the round, except the center toes are slightly longer than described in the round foot, which leaves an oval shaped impression. The hare (rabbit) foot has noticeably longer center toes, all of which are less arched and appears almost elongated. There are then a number of variations on these basic shapes.

Here some may ask what’s the big deal -- why do breed authorities and genuinely knowledgable judges complain about feet on our dogs? The foot is foundational. To illustrate, the Alaskan Malamute breed standard demands a snowshoe foot, which is a specialized variation of the oval foot being well-knit, well-arched, but with strong webbing between the toes. If a Malamute has splayed feet, he is going nowhere fast in his place of origin. Splayed feet are flawed, with toes spread far apart and can occur in any shape of the foot. This may be tolerable in a warmer climate, but in time may prove painful as the Malamute’s weight bears down on the defective foot having spread, far apart toes, typically accompanied by thin, flat pads offering inadequate support.

Consider the various gundog foot shapes, such as the Irish Water Spaniel whose benchmark calls for a large, round, somewhat spreading foot, but never splayed. This separation of toes aids the dog in his primary function, which the breed blueprint clearly defines for working in all types of shooting and who is particularly suited to waterfowling in difficult, marshy terrain. His feet are to have pronounced webbing for propelling him through rough waters, mudflats and tidal marshes with ease. Liken this foot to our using webbed flippers in the water. The greater webbed area propels and the stronger we swim forward. Providing that this dog has the obligatory, moderately spread toes and very strong webbing creating a resourceful surface area, he can navigate through mudflats with ease. An Irish Water Spaniel with short, stubby, well-knitted toes is like poking a stick into the mud.

What of the hunting hounds? Pack scenthound and sighthound feet are highly rated. Consider the American Foxhound, whose feet are of tremendous importance rating 15 points on a scale of 20. His are shaped like a fox foot, which is a variation neither hare nor a cat foot, and is known as semi-hare. This shape levels the playing field so the foxhound hunts with the same shaped digits as his quarry to match speed. He has well-arched toes, close and compact, with thick, tough, pads indurated by use. If you are running a foxhound with a paper or splayed foot, the hound will be useless in the hunt as he will quickly break down.

Lastly, we discuss digital pads and the communal pad. Pads provide protection in the simplest form. They are our shoes. The dog or hound will hurt if he has thin, poorly cushioned toe pads. Experiment by walking barefoot for a long period on various surfaces. Some breeds pride themselves on the size and padding of the feet, e.g., Afghan Hounds. They are to have ridiculously large front feet with harmonious, large, thick pads. As an Afghan Hound judge, I confirm the pads of the front feet because the Afghan Hound hunts in both hot, open, hard packed and steep, craggy terrain. If his pads were small and thin, with a weak fibrous tissue then the hound will break down. In his country of origin, breaking down means the hound most likely will die because speed and hunting skills along with proliferating these traits are necessary for his ongoing value to the tribes.

Keep all these factors in mind when you evaluate your litters because feet are mostly unforgivable.

This article first appeared on the Canine Chronicle website: Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=35454

Head Cases

Depending on the breed, one of the most interesting features is a dog's headpiece. Headpieces glorify the breed by way of expression and shape. �The expression is achieved by appearance, rather the dog’s look, set, shape and color of their eyes, set-on of the ear, the planes of the backskull and muzzle or foreface. What makes a great head case is the handiwork of several important elements. First,...

Depending on the breed, one of the most interesting features is their headpiece. Headpieces glorify the breed by way of expression and shape. The expression is achieved by appearance, rather a dog’s look, set, shape and color of their eyes, set-on of the ear, the planes of the backskull and muzzle or foreface.

So many details go into sculpting a marvelous head. Many breeds are considered ‘head breeds’ insofar as the head is synonymous with the breed’s essence. The headpiece instantly identifies the breed, and fanciers place enormous emphasis on this. Frankly, a glorious headpiece can sway many a judge’s opinions viewing it as the pièce de résistance.

What makes a great head case is the handiwork of several essential elements. First is the formation and length of the bones of the skull. Often fanciers mistakenly refer to the skull as the top of the head encasing the brain. In truth, the skull is the composition of ALL the bony components of a dog’s head, including the upper and lower jaws. In lay terms, there are three scientific classifications for all breeds' skulls derived from the base width and skull length. Their names are not easily pronounced nor relevant for discussion save for one, but their overall shapes are fundamental. The first is a narrow skull base with great length, i.e., Borzoi. Next, the medium base width and proportions of length, i.e., the majority of breeds. The third is most commonly known because of its exaggerations — the brachycephalic skull — which has a broad base and short skull length, i.e., Bulldog.

From here, all due to selective breeding, there is a variety of skull sizes and shapes which set the breeds apart from one another. First, breed blueprints detail the overall headpiece and breakdown its components with specifics. Almost all detail the form of the skull with the most commonly cited being apple shaped, arched, broad, coarse, cone or conical, domed, flat, oval, rounded, and wedge-shaped. Prominent examples of some of these types are the American Cocker Spaniel with a top domed skull and the cone-shaped ideally represented by the Dachshund. The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel demonstrates a top rounded skull, and the Bull Terrier is an example of an oval or egg-shaped skull. Two last good examples are the Collie with a wedge-shaped skull and the Wire Fox Terrier whose brick shaped skull is long and rectangular; its width of the muzzle (foreface) and backskull are nearly the same. Other virtuous and faulty head descriptions include blocky, Fox-like, tapering or squared-off.

The other elements of an ideal head are often the first things noticed. Since I have already discussed eyes and ears with their features — see “The Eyes Have It” and “Hear No Evil” — I will not go into detail about them. I will add though that a poor eye can ruin an otherwise correct headpiece. The eyes are windows to the soul and convey disposition, warmth or otherwise. Eyes and ears are intrinsic for both strong points and beauty, or flaws and ugliness. I recommend both articles for reference.

An ugly or atypical headpiece on an otherwise correct frame, in my opinion, is regrettable. “I just can’t get past that head” is a phrase I often use in my breed, especially if I had to look at it every day. I was schooled by old-timers, those who cherished shape and finesse. For clarification, my origins are in a breed designed in curves; the greyhound-like, Irish Wolfhound whose expression is poignant with a faraway gaze.

Almost all heads are an identifier of a breed. So much so, that if the head were masked or removed from the photo, a dog hobbyist might have a difficult time distinguishing the breed. Conversely, with good reason many learned fanciers say that the working, hunting breeds do not ‘run on their heads.’

This argument is not entirely valid because the skull composes all the head bones, including the jaws. Backskull measurements can determine the width of jaws and formation of dentition. Soft mouths are important in the gun dog breeds and narrow mandibles, or lower jaws are detrimental for hunters, not to mention that it produces wry and parrot mouths. Some believe that faulting a dog’s headpiece, effectively removing him from awards, is likened to ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater.’ However, in some of our ‘head breeds,’ this is not true, as the headpiece is the quintessence of the breed.

Ballyhara Cinneide (Kennedy)

Cinneide -- pronounced 'Kennedy' -- epitomizes the ideal wolfhound's headpiece, take particular notice of her level planes. Here I quote the Irish Wolfhound breed standard:

“Long, the frontal bones of the forehead very slightly raised and very little indentation

between the eyes. Skull, not too broad. Muzzle, long and moderately pointed. Ears, small

and Greyhound-like in carriage.”

This article was first published in an abbreviated version at Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=46838

Hear No Evil

Save for cropped breeds, most fanciers don’t pay too much attention to their dog’s ears, regarding them as obvious features to have but inessential in the overall genesis of a very good dog. Though this may reflect a modicum of reality for a number of breeds, for instance a few sighthounds, where some repeat the phrase parrot-fashion “he does not run on his ears,” indeed there are breeds who contradict this accepted tenet.

‘Hear no evil’ is just one of the principles of a popular ancient proverb. Our canine friends believe they hear nothing but good things from us mostly due to their unwavering dedication and unconditional love for us. Naturally, we are truly fortunate to have such extraordinary carnivores as our closest allies and guardians. As part of their services, their ears perform one of the most important deeds as they hear at higher frequencies than humans. The frequency range of dog hearing is approximately 40 Hz to 60,000 Hz as compared to humans which is 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz, with Hz being the symbol for Hertz, a unit of frequency. Because of this, their alertness has been extremely useful safeguarding us over the millennia.

Save for cropped breeds, most fanciers don’t pay too much attention to their dog’s ears, regarding them as obvious features to have but inessential in the overall genesis of a very good dog. Though this may reflect a modicum of reality for some breeds, for instance, a few sighthounds, where some repeat the phrase parrot-fashion “he does not run on his ears,” indeed there are breeds who contradict this accepted tenet.

There are approximately 36 assorted ear types from our breed blueprints. Due to space limitations, I will not list them, but summarize their shapes such as drop, pendulous and pendant; erect and pricked; or semi-drop, semi-pricked. On occasion, we see judges have a more forgiving attitude towards the not perfect but somewhat flawed ear type on a specimen. I do not disagree with this compromise providing that this does not occur in breeds where the set-on or shape is important to the breed’s function or essence. We must always keep in mind that ear mobility and shape are factors in how well a dog can hear. An ideal illustration is the Ibizan Hound whose rhomboid ears are highly mobile and at times point forward, sideways, or backward according to mood or if hunting.

The placement of the ear lobe or junction to the head is called the set-on or ear set. The shape, leather, carriage and size of ear lobes vary according to breeds, but ears are all the same in composition. The set-on can have an influence on performance, to illustrate, low set ears on a retriever breed may take on water while the dog is swimming to retrieve game. Waterlogged ears are much more prone to infections and are dysfunctional.

Some breeds, such as the Bloodhound and Basset scenthounds, have uniquely shaped ears vital to their ability and competence. Their ears are tools, not only for hearing but are integral parts of the greater apparatus, the head. Heads with loose, pliable, thin skin with deep folds around the face, dewlap, and neck to aid in capturing, holding scent. The length of the ear, even the leather is crafted to cup the scent, while framing his head as it is lowered towards the ground when he is canvassing, constantly puzzling out a line.

Other sorts of ears are considered highlights as they exert great influence on breed essence. Ear carriage on Whippets and Greyhounds, with distinctive rosed ears folded tightly back against the neck, are contributive to expression. Another excellent illustration is the Papillon, with beautiful, butterfly-like ears, either erect or drop, large with rounded tips, and set on the sides and toward the back of the head. The erect type is carried obliquely and move like the spread wings of a butterfly which is a breed trademark though it is acceptable for the drop variety, a wholly drooping ear called Phalene, to be shown in conformation. There are many AKC recognized breeds which are considered ‘head breeds’ with ear lobe attachment, shape and even mobility influential in their expressions. This includes the Great Dane whose head description is 26 percent of the breed standard or the Neapolitan Mastiff whose head is exceptionally distinctive segregating him from the other Mastiff varieties.

Interestingly, Canidae, which are carnivorous mammals that include dogs, wolves, jackals, and foxes, originally all had prick ears. Due to man’s intervention of selective mating and hybridization, the ears dropped on dogs and later domestic foxes species. In Chapter One of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin states

“Not one of our domestic animals can be named which has not in some country drooping ears; and the view which has been suggested that the drooping is due to disuse of the muscles of the ear, from the animals being seldom much alarmed, seems probable”.

This a feature not found in any wild animal except the elephant, states scientist and author Lyudmila N. Trut, Early Canid Domestication, The Farm-Fox Experiment. Mostly, foxes ears became floppy when breeding for tamability and in the process, the researchers observed striking changes in physiology, morphology, and behavior which mirrors the changes known in other domestic animals. Consequently, mankind’s intervention has again proven to be exacting and influential with Trut summarizing,

“Patterns of changes observed in domesticated animals resulted from genetic changes that occurred in the course of selection.”

One message of the proverb “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil, do no evil” is associated with good mind, speech, and action. Another gist of the proverb is turning a blind eye — one that is so very à propos while discussing purebred dog conformation events.

This article was first published at The Canine Chronicle website: Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=39239

He Got a Good Ribbing!

What exactly is the judge feeling for when examining my dog’s chest? Unfortunately, for many exhibitors brave enough to inquire, they do not receive a thorough nor even sufficient explanation. Thus, the reason remains a mystery to many exhibitors. Well, here I will unveil the mystery...

What exactly is the judge feeling for when examining my dog’s chest? Unfortunately, for many exhibitors brave enough to inquire, they do not receive a thorough nor even sufficient explanation. Thus, the reason remains a mystery to many exhibitors. Well, here I will unveil the mystery.

A truly, well-skilled judge is carefully feeling for the curvature or flatness of the ribcage, from the vertebral column down to the sternum. Ribbing is the narrow, elongated bones emanating from the vertebral column that forms the chest wall. The Carnivora, more specifically "Dog", has thirteen ribs on each side, nine sternal and four asternal which connect with the thirteen thoracic vertebrae of the spinal column. The first nine ribs are called ‘true ribs’, the next three -- the tenth, eleventh and twelfth ribs -- are called ‘false ribs’, and the last, the thirteenth rib is known as the ‘floating rib.’ To uncomplicate this, in lay terms the ‘true ribs’ are attached to the sternum, the ‘false ribs’ are hinged at the bottom of the ninth rib and therefore not directly connected to the sternum, and the floating rib -- the shortest rib -- is not connected to the sternum below. Hence, the term ‘floating.’

The shape or contours of these ribs can vary in the many different breeds. To illustrate, well-rounded ribs, also known as barrel-shaped, are well-arched from the upper attachment of the thoracic vertebrae (outwards) to the bottom. An example of this would be the Bulldog, which calls for well-rounded and very deep ribs and is often requested in the stocky ‘Bully’ breeds. The Mastiff also necessitates ribs that are well-rounded with the ‘false ribs’ deep and well set back. A contrasting ribbing shape, such as the Ibizan Hound, requires smooth and only slightly sprung ribs.

The most common rib formation is the egg-shaped or oval-shaped chest which is typical for the majority of breeds. To illustrate, the Briard demands an egg-shaped form, with moderately curved ribs and is not too rounded like the previous working breeds. A formation rarely requested are flat ribs that require less curvature. At the cross section, they lay flat and are not rounded or bowed while radiating downwards. This is illustrated by the Bearded Collie whose ribs, though well sprung from the spine but are flat at the sides or cross sections. This is also true of the Bedlington, who has a deep chest but is indeed flat as the ribs approach the sternum. However, flat ribs are not to be confused with the state of being 'slab-sided' which is narrow throughout. The slab-sided ribcage has very little to no arch, roundness or spring from the spinal column and is flat everywhere, beginning with the articulation from the vertebral and continuing downwards. Both slab-sidedness and flat ribs are atypical for almost all breeds but especially is a serious fault, or antithesis for the endurance hunting dogs such as Beagles, Foxhounds and Wolfhounds. The reason is that rib curvature determines the shape of the chest and influences chest capacity that in turn governs maximum lung and heart development. The flatter the spring or arch of the ribs, the less development of the heart and lungs and tolerance to exercise. Here, I should mention a particular defect in ribbing that is described in the Basset Hound standard, ‘flanged ribs.’ This is a condition in which the ribs are deformed at the bottom, creating a ridge or rim sticking out and it is thought to be common with flat-sidedness. Both of which are faults on a Bassett.

There are other key factors in understanding proper ribbing, besides the shape discussed above. Though all are essential to one another as well as being extremely important. Width often describes chest breadth, as seen in the American Staffordshire Terrier whose blueprint calls for a deep, broad chest. When one looks at the dog from the front, you can observe the well-rounded shape and great breadth of chest. This is the opposite of what you’d find on the Borzoi, who has a rather narrow breadth of chest, although very deep brisket to the elbows, which is depth.

This leads to the next key - depth of chest. The usually desired depth of ribs and chest is to the point of the elbow. In turn, if the chest does reach the point of the elbow it is known as shallow.

The last key factor is the length of the rib cage which frequently is referred to as well-ribbed back, ribbed-up well, well-ribbed up, or long-ribbed back. All of these describe rib cages that are carried or extend well back on the trunk, especially correlating to the length of loin or coupling. Loin or coupling are the powerhouse on a sighthound and their length and depth influences speed and agility. Length of ribbing is crucial for the hunting breeds as it relates to chest capacity that was already discussed. In short, it is vital for superior stamina.

‘Well-developed’ is the compilation of all three key factors including the rib or chest shape. The opposite of being well-developed is known as as being 'shelly' or 'shell-like' referring to a shallow, narrow body, and insufficient chest measurements. For example, the Rottweiler and Standard Schnauzer standards mention these deficiencies as faults.

Summing up, the chest and ribbing are vital as armor for the critical internal organs, i.e. heart, lungs. This armor is key to the development of the organs and in turn, is inextricably linked to endurance and performance. Although we use the expression in jest about ourselves, ‘he got a good ribbing’, in dogs, it is of primary importance.

Ballyhara Rumor

In the photo above, Ballyhara Rumor illustrates ideal symmetry in length of trunk to ribs to loin, as well as depth to elbows and spring of ribs. A seasoned breeder hardly needs to place their hands on the hound to feel that the hound is well-ribbed up and has a powerful arched loin. Notably, also, observe that the thorax is perfectly angled, neither steep nor tubular leaving ample room for the diaphragm's contractions.

This article in ist original version first appeared on the Canine Chronicle website. Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=37508

The Eyes Have It!

Eye color. Much is made of it, but a majority of fanciers have no idea why their breed’s eye color is defined in the breed standard. Other than the cosmetics being the dark eye is considered by most as attractive, many breeders just “do as they are told.”

Eye color. Much is made of it, but a majority of fanciers have no idea why their breed’s eye color is defined in the breed standard. Other than the cosmetics being the dark eye is considered by most as attractive, many breeders just “do as they are told.”

The majority of breed standards demand dark eyes. In truth, for the greater number of our working, hunting breeds, this dark eye color is at odds with nature. There is no greater cultivator, progenitor than Mother Nature. Repeatedly throughout her creations, we find wild animals with light color eyes, predator, and prey alike. Why then do we humans selectively breed and require dark eyes for the better part of our dogs? For basic aesthetic purposes as humans selected for the more pleasant dark eye than the ‘bird of prey’ color, this being amber to yellow. Such light iris color most likely was unattractive but unsettling to our breed forebears, as it was reminiscent of a predator instead of a companion.

Some claim that dark irises permit our dogs to function more efficiently than light, yellow or amber. This is incompatible with Mother Nature. Consider the Lion, an unrivaled predator whose environment is Sub-Saharan Africa, with its savannas and grasslands. This predator’s eye color is golden or amber whose vision is comparable to a human during the daylight hours but has exceptional night-vision. Both the Cheetah and the Tiger irises are golden or yellow with the Cheetah having poor night vision and the Tiger’s approximately six times better than humans. Note that the development level of night-vision depends on the number of the photoreceptor (rod cells) the animal has and has nothing to do with the color of the iris. Further, wildlife biologists state that fur markings under these predators’ eyes aid their hunting vision, indicating whether they are nocturnal, crepuscular or daylight hunters. What of the Wolf, the only ancestor of the canine species whose eye color is typically gold, some amber or light brown and is often seen in hues of yellow, even gray? Even the Eagle, a bird of prey has a pale yellow iris. All these examples have not been disadvantaged with light eyes while performing their function in order to survive.

Ballyhara Kate, 9 months

Selective breeding and aesthetics have had a great influence on the modern breeds. The long-standing preference for dark eyes may already have had lasting repercussions. Such breeding may cause severe selective pressure -- selecting for dark eyes may carry a recessive mutant gene from the trait, along with a dominant normal gene that masked its effects. Such heterozygous dogs would be hidden carriers, unaffected by the mutation themselves but capable of passing it on to later generations. This should be especially concerning amongst breeds with limited genetic diversity.

Insofar as eye setting, frequently referred to as eye shape, incorrect settings can have injurious implications for many breeds. For example, the ideal Rhodesian Ridgeback eye is round, however never protruding as this can be damaging to the hound in his place of origin. The African Bush consists of Buffalo Thorn, Sickle Bush, and other sharp, thorny fauna which could injure and blind a dog whose eyes are bulging. The English Setter eye set specifies that the eye is neither deep set or protruding with the lids tightly fitted so as not to expose the haw. The Golden Retriever eye shape is to be medium-large with close-fitting rims as well and imparts a kind and pleasant demeanor. On the latter, slanting, narrow, triangular, squinty eyes detract from, moreover modify this expression causing the dog to appear mean. As in the Ridgeback, a prominent eye in both English Setters and Golden Retrievers can easily be injured by the brush and picker bush terrain in which these dogs hunt. Particularly at risk are exposed haws that catch debris causing eye infections or more serious, long-term damage.

Eye setting or shape is necessary for the majority of our working dogs. Regarding iris color, Mother Nature knows best, and we should recognize that tinkering with her work has consequences. We must face facts; the eyes have it.

This article was first published on the Canine Chronicle website.Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=36254

His Neck is on the Line

"His neck is on the line." This idiom is appropriate when conversing about show dogs but also specialized breeds. Yes, the neck is more than just another part of the canine skeletal structure that connects the trunk and the head. In truth, it seems to have fluctuating levels of importance depending on the breed.

"His neck is on the line." This idiom is appropriate when conversing about show dogs but also specialized breeds. Yes, the neck is more than just another part of the canine skeletal structure that connects the trunk and the head. In truth, it seems to have fluctuating levels of importance depending on the breed.

In conformation events, the neck can be a showpiece as handlers or exhibitors accentuate or occasionally overemphasize it as exceptional while presenting the dog for examination. It is a familiar sight to watch a handler jerk the dog’s collar up behind the ears while the other hand is stroking downwards on the neck to attract a judge’s eye to both the upper and underlines, subliminally boasting on its length and crest. The Cocker Spaniel or Whippet breed rings are good examples of this as the handler removes the show lead from the dog conferring great flourish on this one aspect of the anatomy. In some cases, such embellishment may be warranted because, in truth, it may be the best part of the dog!

Before I get ahead of myself, a quick anatomy lesson is appropriate. Every dog has seven neck vertebrae, no matter the breed. Attaching the neck and skull are the Axis and the Atlas vertebrae (C1) which allow for head movement. The nape is the skull and neck junction while ‘the blending’ refers to the neck and shoulder junction. Many are unfamiliar with the word 'nape' and the related term ‘crest,’ yet both factor into a number of breeds. Various breeds' fanciers prize a crest; that is a shapely neck whose upper line curves or arches over the Atlas vertebra. Two excellent breed examples are the Scottish Deerhound and the Akita. The Deerhound possesses a prominent nape adding to the beauty of his sighthound curves, and the Akita has an emphasized crest, which blends in with the base of the head, and is reasonably characteristic of the breed.

On the other hand, the neck is a lot more than a showpiece. For some hunting breeds, the neck is instrumental in performance and outcome, as well as safety. The Scottish Deerhounds neck is essential to his function, which is to hold a Stag. His neck is to be powerful and strong, not short and stumpy, but not as long as the greyhound. The greyhound, who has a long, smooth, muscular neck, uses it to stoop while dispatching hare. An Irish Wolfhound will dispatch game by breaking the back of the neck. In order to do this, he must himself have an extremely powerful, hard muscled, long neck, without which, he could become the victim. I included Figure One of an Irish Wolfhound, who illustrates a beautiful, powerful neck whose underline and upper line epitomizes ideal ‘blending.’ The form of this exemplary neck portrays strength and depth — the latter being the distance between the upper line and the underline. The neck is not overly long, weak and

spindly or stuffy, coarse and bunchy. The observer’s eye follows the flow of the neck which enhances the fine topline.

Cudama Santa of Ballyhara

The neck has central muscles coursing from the skull to the shoulder girdle, sternum and rib cage. The Splenius and Sternocephalicus muscles allow side to side motion, extension and lift of the neck. Other muscles lift and move the dog’s limbs, in particular, the Brachiocephalicus, Rhomboideus and Omotransversarius muscles. They work by stretching and contracting, allowing for circumduction of the scapula, shoulder, and upper arm. These are just a few of the vital neck mechanisms that permit the functional dog to perform and excel at his work.

There are approximately fourteen or so descriptions contemplating the varying shapes of the neck that we apply to the many breeds. A few common labels are the bull, ewe, goose, stuffy, 'reachy', and upright neck. Two others specify skin involvement, such as wet and dry necks. A wet neck’s skin is loose, showing wrinkles, throaty with excess dewlap. A dry or clean neck has tight fitting skin without wrinkles and dewlap. A few shapes, which fanciers should be very familiar with, describe either a virtue or a fault. Several are only the opposite of one another such as a reachy neck describes a neck that is of a good length, well-muscled, refined or elegant. This is radically different from a short, stuffy, bunchy, muscled neck. Fanciers tend to confuse ewe and goose neck descriptions, so an explanation is appropriate. The underline of an ewe neck has a slight convex shape (curving outwards) rather than a natural, concave appearance (curving inwards). A goose neck is elongated, round and tubular lacking depth and power. Both of these anatomically defective types have a circumference around the neck and shoulder base similar to that of the skull and neck junction.

In conclusion, breeders perceiving the neck as a mere ornamentation of the skeletal anatomy put their dogs' functional necks on the line.

This article was first published on the Canine Chronicle website,

Short URL: https://caninechronicle.com/?p=40257

Sighthound Necessities

The Importance of Free Exercise for Large Sighthounds

Sighthounds love to gallop, to chase and stretch out. They experience unmistakable, sheer glee as they are bending, folding and leaping. You can see it in their expression. So, why is it that so many of these admirable Sighthounds are found living in unsuitable homes, having little or no fenced, secured acreage?

The Importance of Free Exercise for Large Sighthounds

Sighthounds love to gallop, to chase and stretch out. They experience unmistakable, sheer glee as they are bending, folding and leaping. You can see it in their expression. So, why is it that so many of these admirable Sighthounds are found living in unsuitable homes, having little or no fenced, secured acreage? As responsible fanciers and hobbyists, fulfilling their needs should be a primary concern when we place our hounds in their new, permanent homes. Our stewardship of these unique breeds obliges us to proceed with utmost care and concern while considering a new home.

I am not an elitist who snubs a potential puppy owner, turning up my nose at those whose accommodations are not ideal for our Sighthounds. On the contrary, I encourage them to contact me so that I may educate them about the exceptional needs and characteristics of our breeds. More importantly, though, I am aware that urban population growth has changed significantly over the past 60 years in our nation. We all live in an evolving landscape. "Metropolitan areas are now fueling virtually all of America's population growth," as reported in the Washington Post by Emily Badger. In an interesting article, unwittingly she corroborates what many conscientious breeders have realized, that ideal Sighthound companion homes are harder and harder to find. Small population centers with less than 50,000 people have had infinitesimal growth changes. Rural populations have dwindled. Today, one in three Americans lives within the metro areas of 10 cities — or just a few spots on the nation's map. The relevancy of the census data must not be under-appreciated, as this means that, slowly but surely, there are fewer opportunities for us to find homes for our galloping hounds.

The reality I face is that significantly more inquiries than in the past hail from people with no land. From the 36 puppy requests I have received in the past six months alone, 32 (90%) were from persons who did not have what I consider sufficient area to accommodate a Sighthound. Furthermore, this percentage includes some individuals who either currently have or previously owned a Sighthound — from another breeder — in their home.

I readily anticipate the question "How much land does she require?" Ideally, a home for a large breed Sighthound should have at least one acre of property secured with breed-appropriate fencing, but from my experience of three-plus decades in dogs, this often seems like an unrealistic requirement. A bare minimum of half an acre of open land, again properly fenced, not including the house, is my condition. I have received some requests from potential puppy buyers who own half an acre of land that included the home as well as an accessory building; one memorable inquiry offered half an acre of land that included the house, an in-ground swimming pool with a cabana and what appeared to be a Bocce ball court. All that was left was a postage-sized space for the hound to defecate in, without any area to run and play.

I politely refuse to place my large Sighthound puppies in these environments, notwithstanding the usual promises of the on-lead daily exercise that the hound would receive. You must be familiar with this type of dialog. A potential owner asserts that, although there is no acreage for free running, they regularly walk so-and-so many miles and they also live near a park where the hound can be off-lead. Almost all of us understand that Sighthounds are not candidates for off-lead running on public grounds. Simply, this is a hazardous situation due to their prey drive — a good subject for another article I plan on writing.

As for good intentions and best-laid plans, how many times has life thrown us curve balls? Life has a habit of bringing unexpected, unwanted changes or accidents. If a hound’s principal caregiver is injured or becomes ill, ultimately the hound is handicapped as well. The Sighthound will no longer have lengthy walking excursions to release energy and obtain needed exercise. Likewise, if an owner’s work responsibilities increase, this almost invariably impacts the time spent with the hound on a leash. Regrettably, because the properly fenced acreage was initially sacrificed, the hound does not have an area for self-exercise and running. So, ultimately, he suffers.

Self-exercise for a Sighthound is not only the freedom to stretch out his legs, to leap, twist and turn, all of which releases energy. It also is key to a Sighthound's development, both physical and mental. Strong, hard muscles are vital to proper maturation and longevity, as well as to protecting the body from unwarranted injuries. Secured exercise provides valuable mental stimulation: simply, it is good for a Sighthound's psyche or soul, mind, and spirit. His personality and character can develop to their full potential, which is especially crucial in the powerful, giant Sighthound breeds where it is especially important that they must be even-tempered and well adjusted.

Some may feel that placing companion-quality Sighthounds in a loving home where they receive individualized attention is far better than allowing these hounds to languish in a kennel environment. To a great extent, I agree, but the compromises that some breeders make are worrisome. The trade-offs are unfair and incompatible for galloping hunters bred for running, especially when we hear that Wolfhound puppies are placed in townhomes, not as temporary but as permanent quarters. Where is the line drawn for responsible breeders to reject a potential home?

Others may belittle this discussion by stating that one cannot keep every puppy, and who am I to decide what is enough space for a Sighthound to live on comfortably? Some may claim that leashed exercise is sufficient for our hounds and that many of the hounds exercised only on leash are in better physical condition than a hound with acreage. Now and again, this statement could prove true. Having been a longtime Wolfhound fancier, I know from first-hand experience that, on occasion, some Wolfhounds will not use the available space for running but just sit at the gate. Despite having one hundred fenced acres, there they were, lying on the opposite side of the fence gate waiting for me. On the other hand, Sighthounds living on considerably less acreage may happily explore and bound about their areas.

Today's average homeowner does not have acres of property, in fact, much, much less. For those fortunate to have some but still acceptable amount of property, it can be transformed to accommodate a galloping hound, as long as the homeowner is willing to do so. Indeed, the initial fencing investment is costly, but our sighthound breeds can be expensive. Expenses are a certainty all prospective puppy owners must be prepared for, though, in the end; these hounds are well worth the investment.

Returning to the subject of alternative leashed exercise, I frequently pose this logical question. Which athlete would have the better overall cardiovascular condition? A person who runs or walks daily? Granted, walking is far superior to no workout and also offers benefits. I always recommend puppy owners frequently walk with and socialize their hounds, regardless if they have one or ten acres of fenced land. However, what about the muscle-toning obtained while the Sighthound enjoys fenced but free exercise that is not achieved by just leash-walking? While placing a Sighthound, maybe future fitness is not a priority for some breeders, despite the health benefits. If care, love, and clean accommodations are all that a breeder requires from their puppy owners, they are, in my opinion, doing a disservice to our Sighthounds.

If we cannot respect these breed's noble heritage, why then do we bother having them? There is a myriad of other Group breeds who require only small areas and some exercise who are entirely satisfied residing on the couch. In fact, AKC generates several suggested dog breed lists that correspond to homeowners lifestyles. You can see the links to these from my website page, Irish Wolfhound Breed Character. Several times in these past years, after I called attention to inadequate property conditions and discussed such concerns with a few rational, prospective owners who had fallen in love with the Irish Wolfhound breed, they did, in fact, resist the urge of instant gratification. These people understood my objections; they respected my advice and my decision, recognizing that it would be simply unfair for them to have a giant, galloping hound. As a long-standing breed custodian, a rational resignation like this is one of the best things that I could wish for my wonderful sighthound breed, the Irish Wolfhound.

Prospective Wolfhound Puppy Buyers: Caveat Emptor!

Caveat Emptor Irish Wolfhound Puppy Buyers

8-weeks old is too young! It is unjustifiable and inexcusable to release a wolfhound puppy at such an early age.

I receive periodic inquiries about the Irish Wolfhound breed, and I am happy to share my knowledge with such people. These queries also include requests for advice regarding health issues and nutrition. On several occasions, new owners have reached out to me to ask questions about specific issues their new puppy was experiencing. Delving into the problems further, I had been taken aback when a novice puppy owner told me that they acquired their Irish Wolfhound pup at eight weeks of age! Frankly, taken aback is an understatement. When a caller informed me of this the first time I was momentarily startled, I paused and asked them to repeat what they had just said. After confirming that I heard their unsettling news correctly, I privately assumed that the pup had to have been acquired from a backyard breeder or a puppy mill.

However, after that first time, there have been several others who also reported obtaining their wolfhound puppy at the same very early age, and from various breeders. I fear this has become a profoundly disturbing trend. My previous emotions have now been replaced with alarm. Yes, I am alarmed, and I am not being melodramatic.

It is unethical to place a wolfhound puppy at the age of eight weeks. This act is unconditionally unacceptable for a giant breed Irish Wolfhound, who is underdeveloped — both mentally and physically -- at such an immature stage. It is paramount that Irish Wolfhound puppies are well socialized and spend quality and quantity of time with their Dam and siblings. For other long-standing, conscientious breed guardians and me, it is inconceivable to place a wolfhound puppy before ten weeks of age. Personally, I DO NOT release any Wolfhound puppy before 12 weeks of age.

Mentally, the Irish Wolfhound breed is a slowly maturing hound. His size is very deceiving and just because he or she weighs upwards of 60-75 pounds at three months does not liken him mentally to other breeds of the same age. I have always informed students that this sighthound breed is unlike popular breeds such as Poodles, Golden Retrievers, Labradors or Shepherds, among many others. During growth stages, on a mental comparative basis, for instance, a six-month-old wolfhound is comparable to a three-month-old Labrador. Yes, that much of a difference. Even a yearling -- a phrase attributed to a wolfhound aged 12-24 months -- is still more immature than a similarly aged dog of another breed. The difference has nothing to do with intelligence. An Irish Wolfhound is an intelligent hound who curiously possesses natural foresight, always sensitive to his surroundings. Wolfhound puppies should be confident, poised, comfortable, and friendly. These traits develop from various stimulations deriving from social interactions in the company of his littermates with the dam by their side during their twelve weeks of development and companionship.

For instance, it has long been common knowledge amongst veteran breed guardians that special care, socialization and additional time is usually always required when raising a singleton litter -- just one Irish Wolfhound puppy. Indeed, I know of some older breeders who had a trying time with a singleton that they kept for breeding purposes. Sadly, many modern fanciers know nothing of the old grand breeders knowledge as they have had no maturation under wizened mentors.

Releasing a wolfhound puppy at eight weeks is indefensible. Those precious four weeks stolen from these poor, eight-week-old wolfhound puppies is unique, priceless and it may very well come back to haunt the Buyer. Moreover, releasing wolfhound puppies at eight-weeks-of-age is done so most likely for financial and opportunistic reasons. Commonly, a breeder needs to get rid of the puppies as soon as possible as they cost time, food and money. Often, these people need to move the pups out to make room for new litters and more puppies that are coming or planned. It may be a modern movement acceptable to some unknowledgeable social media participants making feeble arguments in favor of such and who attempt to defend it, but this practice is wholly unsound, heartless and unsafe.

Irish Wolfhounds are a gentle, beloved disposition, sensitive, soft temperament breed who require -- better yet demand -- boundless human interaction. This begins in the whelping box, and ours is NOT a breed to farm out as soon as they become inconvenient for the breeder to have around. If this practice continues, it will only lead down a slippery slope. But, then again, perhaps some self-proclaimed breeders will turn their backs on the breed and jump ship to another one. Finally, if the above factual information does not convince you, then know that breeders who are members of the Irish Wolfhound Club of America (IWCA) are obliged by such membership to the Standard of Behavior for Breeders.

It stipulates, in this protocol, under General Do's and Don'ts:

Breeders should not release a puppy to its new home prior to 10 weeks of age. Elsewhere in this protocol, breeder's must be prepared to give up three months of her/his life caring for the bitch and puppies. The bitch needs supervision and care while in the whelping and nursing phases, and the puppies need constant care and socialization from birth until they leave for their new homes at 10-12 weeks. Moreover, breeders must be prepared to provide the proper care for both the bitch and the litter and to retain the puppies for as long as is necessary to find proper homes, even if that means retaining the entire litter for their lives.

To read the full Standard of Behavior for Breeders, something I strongly recommend all prospective buyers do, follow this link.

Irish Wolfhound Club of America, Inc. Standard of Behavior for Breeders